Introduction

2020 can be said to be a unique year for the Palestinian people. In addition to ongoing settler colonial policies across the occupied Palestinian territory (OPT), human rights violations were committed inside the Green Line. On a daily basis, the Israeli occupying authorities and settlers launched attacks on and violated Palestinian rights. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic compounded the suffering of the Palestinian people, who are deprived of resources and capacities.

Having spread throughout the OPT since March 2020, Palestinians have been focused on controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. In the meantime, however, the Israeli occupying power has seized the opportunity to advance its settler project and intensify repressive measures against Palestinians in all their places of residence, including inside the Green Line and in the West Bank, including the occupied city of Jerusalem. The blockade on the besieged Gaza Strip was further tightened in 2020.

In conjunction with the daily Israeli violations throughout Palestine, the Israeli occupying forces (IOF) continued to confiscate land, demolish structures, displace Palestinians, and construct settlements. The IOF also violated the right to freedom of expression, imposed movement restrictions, and violated the right to health and other economic rights. A set of draft laws were presented to the Israeli Parliament (Knesset), reflecting official government approaches towards Palestinians and the question of Palestine in 2020.

Several draft laws were introduced to formally annex the Jordan Valley and Northern Dead Sea, or northern area of the Ma’ale Adumim settlement. While some legislation proposed annexing all Israeli settlements across the West Bank, other draft laws envisaged the annexation of settlements together with Area C. These and other official legal endeavours sought to illegally annex parts of the West Bank by force to the territory of the colonial state. More recently, in July 2020, a draft law provided for annexing the Jordan Valley and Jerusalem Desert. Many similar draft laws were brought forward to enforce annexation in a way or another. For example, legislative acts were proposed, vesting Israeli ministries, rather than the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA), with the power to provide public services to the Israeli settlements. To this avail, in September 2020,[1] a draft law was proposed to replace the ICA by Israeli ministries to supervise settlements. Although draft legislation has not yet passed, these draft laws reflect the current situation and political consensus within the occupying Power.

Regardless of its form and scope, de jure annexation has been an object of general agreement in the occupying state of Israel. In 2020, annexation was closer than ever. Experience shows that even though it did not take place in 2020, annexation will likely be implemented in the coming years. This is evidenced by the Basic Law: “Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People, which was tabled in the Knesset for the first time in 2011, but was later enacted in 2018.”

Internally, no positive developments were seen in practices of the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Gaza-based de factogovernment towards Palestinians. In relation to civil, political and economic rights, the situation only worsened owing to COVID-19 and the measures taken by Palestinian authorities to limit the spread of the pandemic. In particular, since the beginning of March 2020, a state of emergency has been recurrently declared and extended on unlawful grounds. Freedoms, especially the right to freedom of expression, continued to be suppressed. Economic rights also deteriorated due to the economic downturn caused by closures.[2] Opportunities for accomplishing Palestinian national reconciliation, unity, and project have dwindled.

This report addresses Israeli violations of Palestinian human rights. It mainly covers Palestinians killed by the IOF and demolitions of private and public structures, all of which Al-Haq documents comprehensively. The report provides a non-exhaustive account of many other Israeli violations, including raids, arrests, movement restrictions, and confiscations. Additionally, the report highlights violations committed by the PA in the West Bank and the de factoauthority in the Gaza Strip. It presents violations documented by Al-Haq, including arbitrary detention, impingements of the right to humane prison conditions, right to a fair trial, and right to freedom of expression.

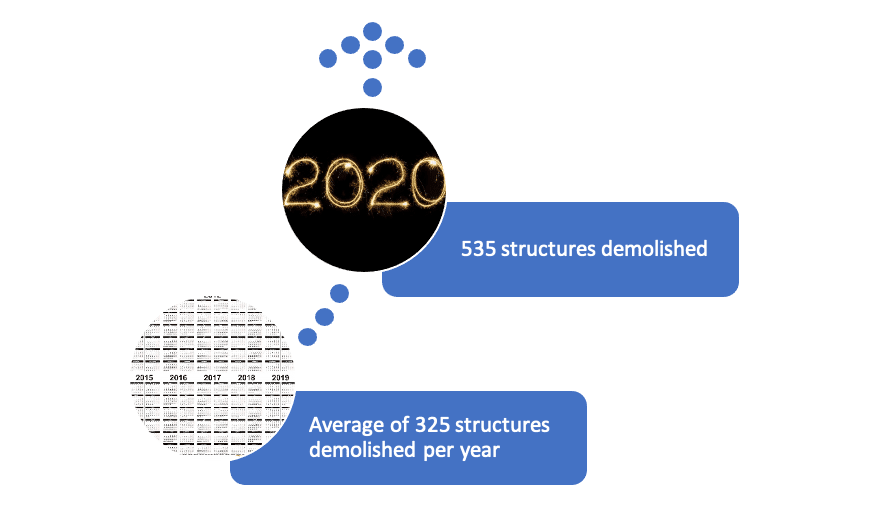

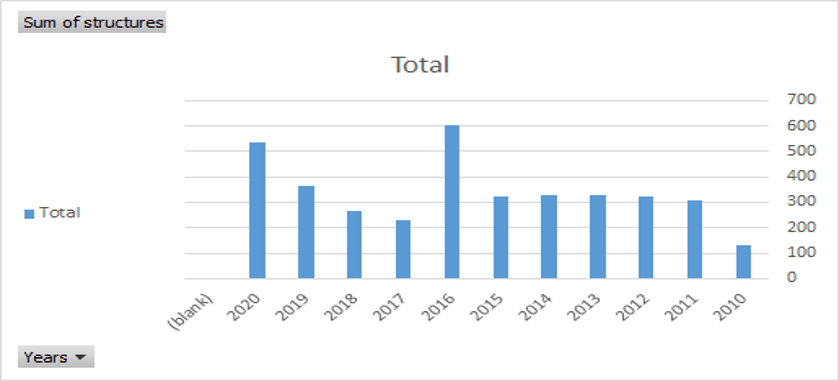

Perhaps most remarkable of all Israeli violations in 2020 was the increasing frequency of demolishing Palestinian private and public structures, amounting to twice the average number of structures destroyed on annual basis over the past 10 years. This reflected unrestrained Israeli policies during US President Donald Trump’s final year office. Israel’s impunity was further encouraged by the international community’s neglect of Israeli colonial policies.

Below is an account of key human rights violations in 2020 as documented by Al-Haq.

I. Israeli violations

Killings

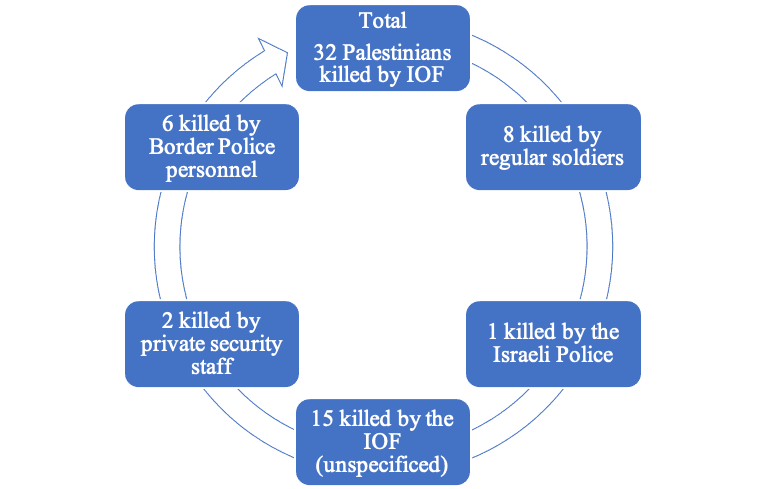

Excluding deaths inside Israeli prisons, in 2020, 32 Palestinians were killed by the IOF. These included nine children and one woman.

While IOF soldiers implemented a shoot-to kill-policy with impunity, an Israeli draft law was proposed in 2020, inhibiting the ability to hold to account soldiers who killed Palestinians during their military service.[3] The draft law is still in the initial stages of approval, and has not yet been enacted. However, in addition to promoting a culture of impunity, the draft law encourages IOF troops to utilize force, in violation of international law, without any expectation of accountability.

Below is a distribution of Palestinians killed by the IOF and related personnel according to perpetrators:

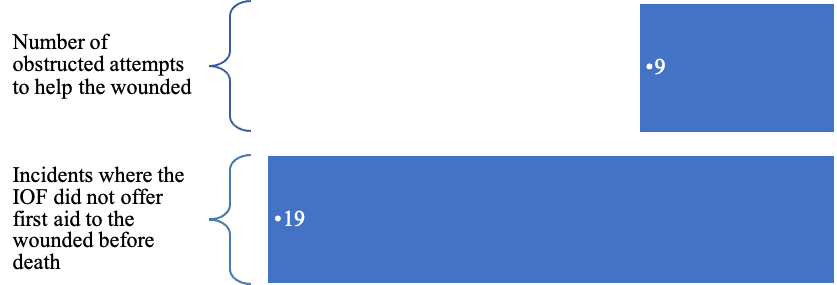

On nine occasions, IOF soldiers prevented Palestinian ambulances from accessing and providing first aid to Palestinians before they succumbed to their wounds. In 19 cases, reflecting the majority of Palestinian’s killed in 2020, IOF soldiers did not offer any first aid to wounded Palestinians after they had been shot. No ambulances managed to reach the wounded.

A total of 16 Palestinians who were killed sustained bullet wounds in the upper part of the body or were hit by multiple injuries, including in the upper part of the body. Only two Palestinians died of injuries sustained in the lower part of the body. The injuries of 14 of those killed were unspecified, including for such reasons as withholding their bodies. In sum, the vast majority of injuries were sustained in the upper parts of the body.

In 2020, the Israeli occupying authorities withheld the bodies of 18 Palestinians. The bodies of 69 Palestinians continue to be withheld towards the end of 2020. Since the policy was reintroduced following the October 2015 uprising, a total of 245 bodies of Palestinian’s have been withheld for various periods before they were released. The longest-held body was apprehended on 20 April 2016. It should be noted that a number of bodies belonged to Palestinians who died in Israeli prisons. The Israeli occupying authorities refuse to release their bodies until they fully serve their prison sentences regardless of the fact that they are dead. Most recently, the Israeli authorities withheld the body of Kamal Abu Wa’ar, who died as a result of illness on 10 November 2020. Arrested in 2003, Abu Wa’ar was sentenced to six terms of life imprisonment as well as 50 years in prison. The above figures do not include those bodies held in the so-called Cemetery of Numbers. According to the Jerusalem Legal Aid and Human Rights Centre (JLAC), 253 bodies of Palestinian’s have so far been withheld in this cemetery.[4]

In this context, an Israeli draft law was proposed prohibiting the release of bodies of Palestinian’s who were members of any Palestinian faction.[5] At the same time, the Israeli Cabinet endorsed a proposal by the Israeli Minister of Defence, Benny Gantz, to prevent handing over the bodies of Palestinian’s who had carried out operations against the Israeli occupying authorities regardless of their political affiliation and nature of the operation. This proposal superseded a former policy, which prohibited the release of bodies of Palestinians who had been members of Hamas and carried out operations against the occupying state of Israel.[6]

The following highlights the killing of Iyad al-Hallaq (32), a young, disabled Palestinian man. On 30 May 2020, Al-Hallaq was killed at the Lion’s Gate to the Old City of occupied Jerusalem. Addressing the circumstances of his death, Al-Haq investigations demonstrated that IOF soldiers extra-judicially killed Al-Hallaq while he was lying on the ground and trembling with fear.

In her sworn testimony to Al-Haq, W. A. recounts:

Before I reached the dumpster on the junction to the Remission Gate, I heard a voice in Hebrew, which I understood: “Vandal, Vandal”. Behind me, I saw three Border Police officers of the occupying army. I also saw Iyad al-Hallaq, one of my students at the Elwyn School, running away. I shouted at Iyad to stop running. At the same time, I shouted at the Border Police officers in Hebrew and Arabic: “Disabled. He is disabled”. However, my calls were not answered. I did not hear any word of caution addressed to Iyad, telling him to stop. Suddenly, I heard gunshots, but did not know how many bullets were fired. At that time, I had reached the municipal dumpster and saw a cleaner there. “Come and hide here,” he told me. I hid behind a barrel. Meantime, Iyad was running. I saw him falling on his back in the yard. He was bleeding from his foot, but I did not know which one in particular. Three Border Police officers arrived. One of them carried a gun and shouted at Iyad and me :“Where is the pistol?” I told him I did not have a gun. I said in Hebrew and Arabic that Iyad was a person with disability. However, he continued to point the gun at Iayd and me. Iyad pointed at me and shouted “I’m with her.” This situation continued for about five minutes. Then, I saw the Israeli Border Police officer with the gun shooting three live bullets at Iyad from a distance not exceeding five metres. The Border Policy officer was standing at the entrance to the yard and did not come close to Iyad. Iyad used to work with me in the school’s kitchen unit in order to rehabilitate and integrate him into society. He was 32 years old, but his mental age was just seven years. On the day of the incident, he did not carry anything in his hands. He put on a blue mask and black gloves. He dropped them when he fell on the ground in the yard.[7]

Deaths in peculiar circumstances and indirect killings

Eleven Palestinians were killed in peculiar circumstances. Of these, four Palestinian political prisoners died in Israeli prisons. These were believed to have been killed as a result of medical negligence. Two Palestinians died of heart attacks while IOF soldiers chased them along the Separation Wall. One Palestinian died because the Israeli occupying authorities had not issued him a permit to exit the Gaza Strip for medical treatment in a hospital in Jerusalem. Another was killed by Israeli explosive remnants of war (ERW). The man found and attempted to dismantle an ERW, which exploded and killed him. In two separate incidents, a young man and woman were also killed in peculiar circumstances. It has not yet been established that they were killed by IOF soldiers. Finally, one Palestinian was killed inside an Israeli settlement, but there has not been any confirmation of who the perpetrator was.

Demolitions

|

Figure 1: A home demolished in Yatta, Hebron, November 2020 |

In 2020, the IOF demolished a total of 535 private and public structures, marking a significant increase in comparison to the average of the previous 10 years (2010-2019). During that period, the annual average of demolitions was close to 325 structures. In 2020, the number of demolitions was higher by an average of 210 additional structures.

Demolitions and displacements are on the rise. According to Peace Now, in 2020, the Israeli occupying authorities announced tenders for the construction of 3,512 housing units in Israeli settlements across the West Bank, including in the occupied city of Jerusalem.[8] The Israeli authorities further expanded settlement activity through draft laws, which provided for resettlement in four small settlements, which were evacuated in the context of the 2005 Disengagement Plan. In line with Al-Haq documentation, however, Israeli settlers did not abandon some of the evacuated settlements, but remained in the areas surrounding them. In particular, it has been constantly monitored that Israeli settlers continued to be present around the evacuated settlement of Homesh and continue to assault Palestinians.

According to the Abdullah al-Hourani Centre for Studies and Documentation, in 2020, the IOF confiscated 20,030 dunums of land for settlement expansion throughout the OPT.[9] At the same time, draft laws were introduced with the aim of limiting the possibility of restoring even small areas of Palestinian land in any future settlement process. Other draft laws provided for the confiscation of privately owned Palestinian land, on which Israeli settlements have been constructed.[10]

At the same time, the Israeli occupying authorities continued to demolish Palestinian structures inside the Green Line. The latest indications suggest that as many as 50,000 Palestinian homes are at risk of demolition[11] under the Chemnitz Law, which was approved several years ago to restrict Palestinian construction. Thanks to unrelenting efforts to resist the legislation by Palestinians inside the Green Line, the law was partly and temporarily suspended.[12]

Homes[13]

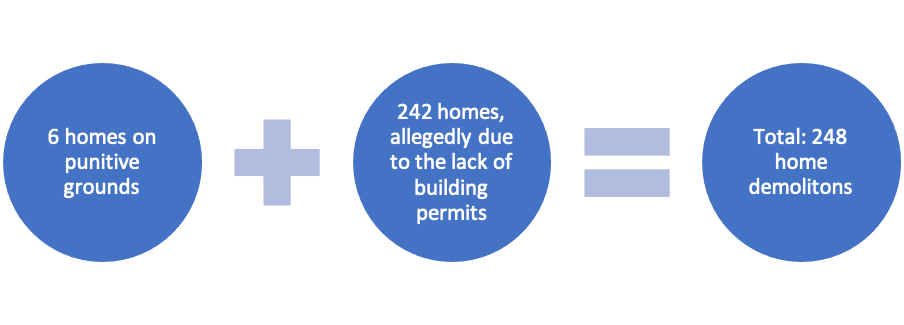

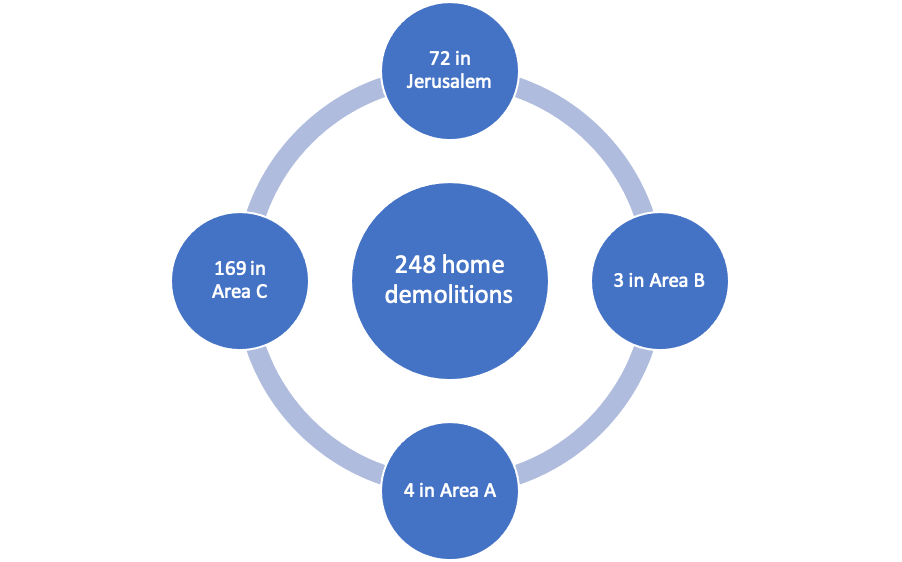

During the reporting period, the IOF demolished 248 homes, representing a sharp rise in comparison to 180 homes destroyed in 2019. The vast majority of affected Palestinian homes (242) were demolished citing the lack of Israeli-issued building permits. Six homes were demolished on punitive grounds.

Seventy-two (72) demolished homes were located in the city of Jerusalem, 169 in Area C, three in Area B, and four in Area A.

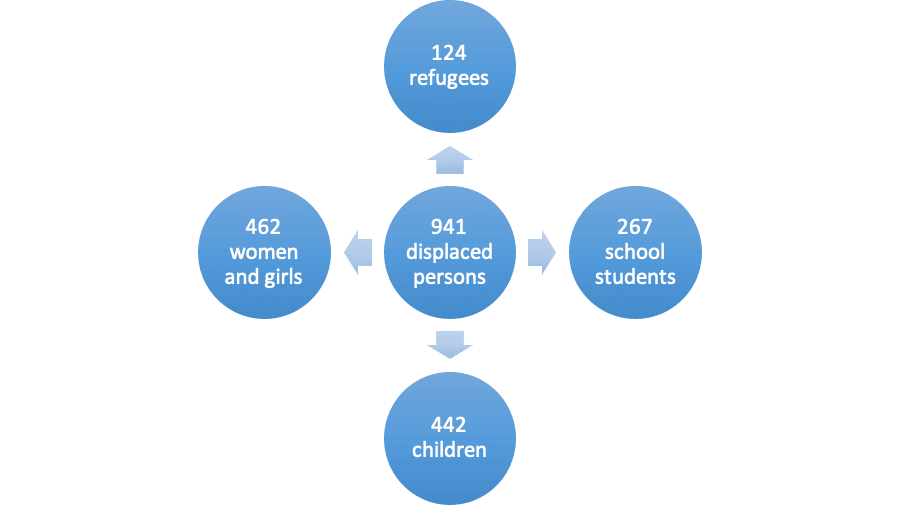

Home demolitions resulted in the displacement of 941 persons, of which 462 are women and girls, 442 are children, 267 are school students, and 124 are Palestinian refugees already displaced from their original homes.

Palestinians are allowed to file petitions to the Israeli High Court against Israeli displacement policies. However, these petitions serve little purpose as the High Court serves to perpetuate the colonial regime. Additionally, the Israeli occupying authorities have made unremitting efforts to constrain Palestinians’ ability to access recourse at the High Court. The last of these was a draft law, which prevents human rights organisations or any other unaffected party from submitting petitions to the High Court on behalf of affected Palestinians,[14] rendering difficult recourse to the Court which overwhelmingly renders judgements in favour of the occupying Power. However, international law prevents the Israeli occupying authorities from extending the jurisdiction of its courts to the occupied territory. In fact, the reason for this Israeli practice is not attributed to attempts to cripple the ability of Palestinians to go to Israeli courts. Rather, it lies in Israel’s attempts to prevent Palestinians from using these formal tools to defend themselves against Israeli practices.

While 55 were under still construction, 193 of the demolished homes were already completed. The majority of the latter were inhabited. The Israeli occupying authorities did not allow an opportunity to the home owners of 69 homes to evacuate their belongings from their homes before the demolitions were carried out. Having received demolition notices, the owners of 118 homes lodged objections to official Israeli authorities to prevent the demolition of their homes. However, these homes were demolished. Fifty-four (54) families had other homes, which had also been demolished earlier.

During home demolitions, members of 27 affected families were violently harassed, attacked, or physically assaulted. Partial curfews were imposed during six incidents of home demolitions. At the time of demolition, three demolished homes were not owned by their inhabitants, causing loss for both the residents and the homeowners. After their homes had been demolished, the vast majority of affected families had to rent residential flats or sought refuge in their relatives, friends or neighbours’ homes until such time they could rent a shelter.

|

Figure 2: A home demolished in Yatta, Hebron, December 2020 – Al-Haq |

Self-demolitions are also on the rise,[15] particularly in the occupied city of Jerusalem. In 2020, 49 homes were self-demolished, marking a dangerous escalation of this practice over the past years. Self-demolitions are triggered by the pressure placed by the Israeli occupying authorities. To avoid hefty costs and fines charged by the Israeli Jerusalem Municipality on structures at risk of demolition, the owners are coerced into demolishing their homes by themselves.

Other private structures[16]

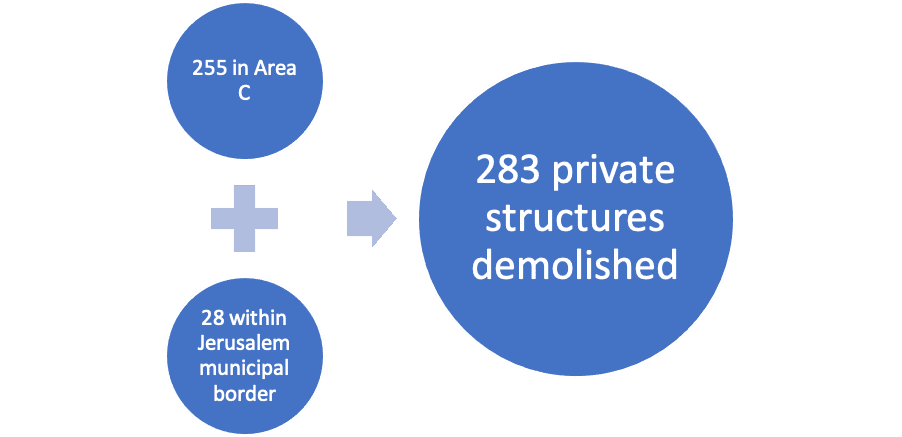

Compared to 169 in 2019, a total of 283 private structures were demolished in 2020.

Of these, 255 structures were located in Area C, so designated by the Oslo Accords, and 28 within the Israeli municipal borders of Jerusalem.[17]

Of all demolished private structures, 139 structures had been used to provide a main source of livelihood to affected family members. These comprised workshops, small factories, animal shelters, poultry farms, and greenhouses. At the time of demolition, 27 private structures were under construction; the others were finished buildings. Published in early 2020, a report by Haaretz indicated that, out of 1,485 Palestinian applications for construction in Area C in 2016-2018, the Israeli occupying authorities only approved 21, or approximately 1 percent of all applications.[18] Sixty-eight (68) owners of structures with demolition notices filed challenges against the demolition of their property. However, the Israeli occupying authorities rejected these official petitions and demolished all affected structures. This indicates that recourse to legal mechanisms, which the occupying state of Israel claims that Palestinians can use, does not change Israeli policy. It demonstrates that the Israeli legal apparatus is an institutionalised aspect of the occupation regime.

|

Figure 3: A wedding hall demolished in Khirbet Jubara, Tulkarem, September 2020 |

Before their private structures had been demolished, 81 affected families were subject to other human rights abuses and attacks by the IOF. These violations were not necessarily related to demolitions. For example, prior to the documented demolition, the IOF had demolished other structures or killed, arrested, or assaulted members of these affected families. Of all demolitions, 42 structures were destroyed for at least the second time after they had been reconstructed and affected families had recovered from previous demolitions. The owners of 149 structures reported that the Israeli occupying authorities did not allow them an opportunity to evacuate their possessions before demolitions were carried out.

Public properties

The Israeli occupying authorities demolished four public facilities, including three in Area C and one in Area B, so designated by the Oslo Accords. Demolished properties included a tent erected for sit-ins in protest against Israeli practices in the town of Dura, foundations of a school, a classroom, and a concrete perimeter wall of a football playground under construction.

Three public structures were located in close proximity to settlements or areas under the threat of settlement construction. The total cost of all four demolished public structures was nearly NIS 451,000 (136,468 USD).

The affected public properties covered an area of some 675 square metres. The cement perimeter wall was 275 metres long. These structures were demolished by bulldozers produced by Volvo and Hyundai. Al-Haq could not ascertain the types of machineries used in the rest of demolitions.

|

Figure 4: A demolition in Shu’fat refugee camp, June 2020 |

All four demolitions were carried out by the ICA with support from the IOF. While two were under construction, two public structures were already completed at the time of demolition. Of the four incidents, the Israeli occupying authorities delivered demolition notices for two structures. The others did not receive any notices before the decision on demolition was implemented.

Other Israeli violations[19]

The IOF and Israeli settlers committed hundreds of other violations throughout 2020. According to Al-Haq documentation, in addition to killings and demolitions, the IOF perpetrated more than 1,000 other violations, including arrests, confiscation of property, injuries, house raids and searches, beatings, physical violence, and torture. The IOF also assaulted medics, denied access permits or permits to receive medical treatment, placed restrictions on the rights to freedom of movement and peaceful assembly, and committed environmental violations.

|

Figure 5: Crops damaged by pesticides sprayed by the Israeli occupying authorities in Khuza’a, January 2020 |

Of all other Israeli perpetrators, Israeli settlers committed the greater portion of violations. Most notably, Israeli settlers stoned Palestinian homes and pedestrians, leaving many Palestinians with injuries. Settlers also attacked Palestinian communities, sprayed racist graffiti on walls and vehicles, and damaged wheel tyres. They made multiple attempts to seize control of Palestinian privately owned land, and harassed and prevented Palestinians from accessing their land. Of particular note, Israeli settlers set fire to Palestinian trees and crops, cut down and uprooted trees, and stole harvest.

A major portion of Israeli settler attacks targeted Palestinian villages in the Nablus governorate, particularly those in the area surrounding the settlement of Yitzhar. Israeli settler violence affected dozens of Palestinian communities.

According to Al-Haq documentation, the most notable Israeli violations can be categorized as follows:

|

Categories of violations by Isreali duty bearers |

|

|

Abducting persons and children |

Flooding agricultural land with water and wastewater |

|

Arrests |

Forced expulsion |

|

Arson of planted fields and trees |

House raids |

|

Assaults on fishers |

House searches |

|

Attacks on hospitals |

Ill-treatment and torture |

|

Attacks on universities and schools |

Imposing collective punishment on communities |

|

Attempting to seize land by creating facts on the ground |

Insults and humiliation |

|

Ban on travel |

Killing |

|

Beating and physical violence |

Land confiscation |

|

Bullet/rubber coated steel bullet wounds |

Levelling lands and trees |

|

Chasing workers |

Movement restriction/denial between cities |

|

Closing commercial premises |

Mutilation of dead bodies |

|

Closing down cultural associations |

Obstructing the work of journalists |

|

Confiscating agricultural vehicles and tractors |

Opening fire |

|

Confiscating electronic devices |

Preventing farmers and workers from accessing their workplaces |

|

Confiscating/looting archaeological artifacts |

Punitive demolitions |

|

Confiscating/steeling money |

Raiding Palestinian cities and towns |

|

Confiscation of equipment and machinery |

Running over livestock |

|

Constructing settlement outposts |

Seizing control over water wells and sources |

|

Cutting down and uprooting trees |

Setting fire to private and public structures |

|

Damaging agricultural crops |

Setting fire to private vehicles and properties |

|

Damaging fishing boats |

Setting up flying checkpoints |

|

Damaging homes during search operations |

Settlement expansion |

|

Damaging vehicles |

Sinking fishing boats |

|

Deliberate vehicular ramming attacks |

Spraying lands with herbicides |

|

Demolishing private structures and homes |

Spraying racist graffiti |

|

Demolishing public structures |

Stabbing attacks |

|

Denial of access permits |

Stealing crops |

|

Denial of access to privately owned land |

Stealing livestock |

|

Denial or delayed approval of permits to receive medical treatment |

Stealing olives |

|

Destroying water pipelines |

Stone throwing at homes and vehicles |

|

Direct hit by sound/tear gas grenades |

Suppressing peaceful assemblies |

|

Extortion |

Withholding the bodies of martyrs |

While on the ground, Israeli occupying authorities worked towards legalising these colonial practices at both the legislative and policy levels within the occupying power. In this context, at least three draft laws were proposed with the aim of limiting the possibility of releasing Palestinian detainees. These legislative proposals primarily provided for releasing one detained Palestinian for every Israeli prisoner. This is designed to avoid earlier incidents, which involved the release of thousands of Palestinian prisoners in return for a limited number of captive IOF soldiers.

To further tighten Israel’s colonial grip, a draft law was submitted to suppress the Palestinian right to resistance against the Israeli colonial occupation. This legislative act sought to legalise expulsion of the families of Palestinians, so-called “vandals”, who carry out operations against the Israeli occupying authorities outside Palestine. This is a more egregious form of collective punishment imposed by the Israeli occupying authorities on the families of those charged with carrying out operations against the Israeli occupation.

In the context of the occupying Power’s unrelenting efforts to suppress the right to freedom of expression, particularly arguments against colonial practices, a draft law was presented to the Knesset with the aim of amending the so-called Anti-Terrorism Law. A provision would be added, prescribing a five-year imprisonment for any person who publishes or ‘likes’ a post on social media networks supporting Palestinian rights and struggle for independence, as enshrined by international law.

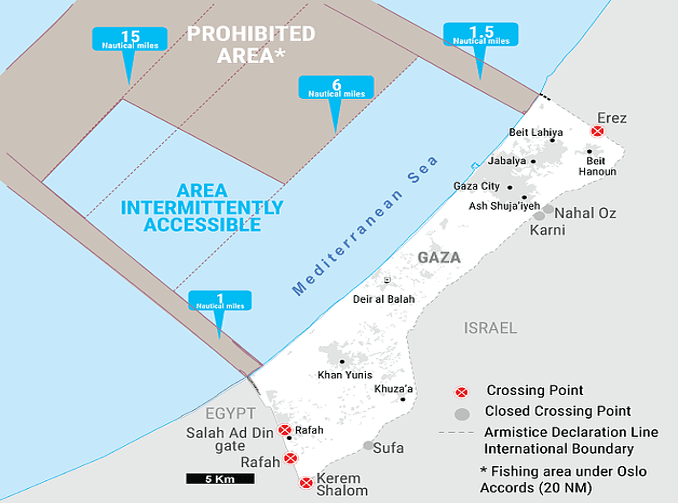

This report places a special focus on Israeli attacks on Palestinian fishers in the besieged Gaza Strip. In 2020, Al-Haq monitored over 73 Israeli attacks on Palestinian fishers off the Gaza coast. These included sinking fishing boats, chasing, arresting and opening fire on fishers, and seizing fishing equipment and boats.

Although the Oslo Accords allow Palestinian fishing within 20 nautical miles (approximately 37 kilometres) off the Gaza Strip coast, over the years, the Israeli occupying authorities have reduced and prevented Palestinians from fishing within this area at all. The Israeli authorities officially have permitted fishing within six and 15 nautical miles north and south of the Gaza Strip, respectively, over the past years. However, access to these areas is restricted intermittently, and without warning, depending on developments on the ground. According to Al-Haq documentation and monitoring in 2020, the majority of Israeli attacks on Palestinian fishers took place within the reduced area (six and 15 nautical miles north and south of Gaza), which is ostensibly allowed by the occupying state of Israel for Palestinian fishing.

|

Figure 6: Source: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

In his sworn statement to Al-Haq, R. S. a fisherman, reports on the violations fishers are subjected to. R. S. recounts one incident:

At about 3:30 pm, we were done fishing. We headed north in order to return to the Gaza port. When we were off the Deir al-Balah beach, Central Gaza governorate, and at a distance of seven nautical miles within the permissible area, I saw three Israeli gunboats (one large cruiser and two rubber boats) approaching us from the west and north. The Israeli naval boats surrounded our boat from several directions. Navy officers on board the boats fired rubber coated steel bullets on us from a distance of some six metres. I was hit by a rubber coated steel bullet in the left knee. Majed Miqdad was shot in the right side of the waist and another in his back. My nephew, Ali, was extremely frightened of the horrific incident and sought protection under the engine on board the hasaka (fishing boat). Then, the navy officers ordered us to take off our clothes immediately and jump into the cold water. Indeed, Majed and I jumped into the water, but Ali remained on board the boat because he was so scared and shocked. Majed and I got on board a small rubber boat. The officers on the second rubber boat arrested and put Ali on their boat. They tied the fishing boat with a rope to the rear part of the boat. They seized our boat from us, including fishing nets and equipment. Later, the officers blindfolded us and tied our hands with plastic handcuffs. The rubber boat sailed for about 10 minutes. Meanwhile, we were only in our underwear and it was so cold. When the boat stopped, they removed the blindfolds and handcuffs and moved us to the large cruiser. Then, they gave us clothes (blue and red pants and sweaters). After we put on the clothes, they blindfolded and handcuffed us once again. The cruiser then sailed for almost an hour and 15 minutes. When it stopped, the officers lifted the blindfolds a little bit and dropped us on the Ashdod wharf. I knew the port because I had been arrested twice during my fishing activity. When we were off the cruiser, the officers blindfolded us again and took us to a place inside the port. They left us sitting on the ground for many hours while we were blindfolded and handcuffed. They did not bring in any food or drinks for us. Meantime, we were examined by a doctor while we were also blindfolded and handcuffed. They doctor did not care about Majed’s and my injuries despite the pain we felt and the swelling at the place of injuries. Late at night, they put our hands and feet in iron shackles, removed the blindfolds, and took us to a bus, which drove to the Beit Hanun (Erez) crossing, north of the Gaza Strip. There, we were subjected to an intimate body search and briefly interrogated about the reason of our arrest and family members. At about 11:30 pm on the same day, we were released. They confiscated the fishing boat together with the fishing equipment and nets. The cost of these is nearly US $ 15,000. We have lost our only source of livelihood and subsistence of our families. This was despite the fact that we were fishing within the permissible fishing zone.[20]

In another statement, M. Z., a fisherman, reported to Al-Haq:

At about 4:45 pm, I saw the swift Israeli rubber boats chasing fishing boats to our west and forcing them to head south in order to keep them away from the area. I was assured because I was working within the permissible area near to the beach. While the Israeli boats were chasing fishing boats which managed to escape to the south, a small rubber boat approached us. Israeli navy officers fired rubber coated steel bullets on us while I was trying to pull the fishing nets out of the water in fear that I would lose them. Then, I was hit by a rubber coated steel bullet in the thigh. My little brother, Maysarah, was too frightened and panicked by the horrible shooting incident. It was the first time he came with me on a fishing trip. Meantime, my fishing nets were torn apart and sank into the sea. A number of fishers also lost their nets as the Israeli boats chased them and deliberately ripped apart and sank the nets into the sea. Later, I managed to get back to the beach and returned home as quickly as possible because I felt immense pain at the place of injury.[21]

Fisher Y. A. recounted his experience, stating:

I was surprised by two Israeli military launches, which had arrived and surrounded our boat. One launch turned around and stopped at a distance of almost 15 metres opposite our boat to the east. This was known to us as the Super Dvora. The other, which was larger and known by the name cruiser, stopped at a distance of about 15 metres to the west. On board the two launches, I saw a number of soldiers, including six on the small boat and nine on the large one. They were in black uniforms and heavily armed. Over a loudspeaker, I heard a soldier shouting at us in Arabic: “Stop and don’t move.” A few moments later, the large boat which stopped to the west pumped water forcefully on our boat. While I held the boat engine, my brother Ibrahim and brother-in-law Saleem grabbed the boat and tried to maintain its balance so that it would not sink. The boat continued to pump water on us for about 25 minutes. Meantime, I felt that my hand was injured and felt pain due to the strong water thrust. Still, I did not leave the engine so that I could keep balance of the boat. At that time, I saw our equipment falling off the boat into the sea, including fishing nets and 60-litre gas gallons. Water filled the boat, which was about to sink. Over the loudspeaker, I heard a soldier shouting: “I will make an example of you to all fishers of the Gaza Strip.” Both boats moved over after the cruiser pulled and confiscated the nets. Then, I saw them attacking another fishing boat at a distance of about 40 metres to the west. Four fishermen who were residents of the Gaza city were on board that boat. I realised that from the distinctive yellow colour of the boat. It is known that yellow was the colour of the Gaza city port. The two boats turned around, attacked, and started to pump water on the boat for almost five minutes. As a result, the boat turned over and I saw all four fishermen falling in sea as well. Immediately, fishermen around us rushed to help and managed to rescue them. A number of fishermen also arrived and helped us empty the water from our boat. They tugged my boat to the Khan Yunis port because the engine had broken down. When we arrived at the beach, I was transported by a civilian car to the Nasser Governmental Hospital west of Khan Yunis. After a medical check, it appeared that I sustained a bone fracture in a finger on my left hand as well as contusions and muscle rupture in the back. I received treatment for four hours. Doctors bandaged my hand and I left the hospital. After I came back, I checked my boat and the damage caused to it. The engine broke down. I also lost the boat tarp and all fishing tents, including eight cage traps and two sardine nets, 60 litres of gas, and 60 kilos of fish I had caught. The estimated cost of my losses was around US$ 3,000. I should note that we are frequently chased. Although we do not go beyond the permissible fishing zone, fire is opened around our boats by Israeli military launches while we are fishing. Almost two months ago, I was chased by an Israeli military launch, which opened fire around my boat. I was at a distance of some four nautical miles west of Khan Yunis. I was forced to leave a 50-metre long fishing net in the sea and leave for the beach in fear that I get injured or arrested.[22]

Violations by the Palestinian Authority and de facto authority in the Gaza Strip[23]

In 2020, Al-Haq documented hundreds of violations committed by the PA and the de facto authority in the Gaza Strip. Of particular note, abuses of the PA and the de facto authority were perpetrated under the guise of the state of emergency unlawfully declared and extended by the PA President, beginning on 5 March 2020 towards the end of the reporting period.

Violations were of multiple forms. Most prominent were arbitrary detention; infringements on the right to a fair trial, right to humane prison conditions, and right to freedom of expression; ill treatment, torture; beating; physical violence; and confiscation of devices, funds, and equipment.

The table below shows the distribution of violations documented by Al-Haq:

|

Violation |

Number of violations |

|

Arbitrary detention |

100 |

|

Violation of the right to a fair trial |

71 |

|

Violation of the right to humane prison conditions |

145 |

|

Violation of the right to freedom of expression |

37 |

|

Ill-treatment and torture |

52 |

|

Beating and physical violence |

49 |

|

Confiscation of devices, funds, and equipment |

30 |

A. D. recounts his experience during arbitrary detention:

At about 2:00 pm on Sunday, 13 December 2020, I received a call on my mobile telephone. The caller identified himself as a Palestinian Preventive Security officer in the city of Nablus and told me that I would have an interview on Tuesday, 15 December 2020… In the evening on Monday, 14 December 2020, I fell ill due to tendon rupture in the left foot… As a result, I stayed at home and did not go to the Preventive Security on Tuesday… I decided to go to the interview with and report to the Preventive Security as per their summons in fear that they would raid my home and arrest me from there. At about 11 am on Wednesday, 16 December 2020, I went to the Preventive Security Directorate in Nablus… I was brought into a room, in which there was an officer who did not introduce himself. I sat on a chair and he at a desk with a computer set as well as papers and files in front of him. The interrogation session started when the officer asked about my personal details. He then asked about my detention by the Israeli occupying authorities as I mentioned earlier. He engaged with me in discussing the reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas, and was of view that the reconciliation would not be achieved and that it would fail… About 15 minutes later, he asked me to go back to the waiting room and said he would call me in. Indeed, I went to the waiting room, where I stayed for almost 45 minutes. Again, I was summoned to the same interrogation officer in the same room. He began interrogating me about the Islamic Bloc activities at the An-Najah National University and talked to me about the anniversary of the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas), which was marked on 14 December 2020. I said to the officer I did not have anything to do with these activities or with Hamas. I was detained by the Israeli occupying authorities, fell behind my university studies, and had exams that I wished to take. During the interrogation, the officer was taking notes of my statements that I had nothing to do with his claims. Then, another interrogator got in and also talked to me about political issues and the reconciliation. I told them I had nothing to do with that. “I do not care what you are talking about”, I said. About 40 minutes of interrogation, I was asked to go to the waiting room. Almost half an hour later, a jailer arrived, asked for my personal belongings, and searched me from the top down. “Why?” I asked. “You are under arrest,” he said… The jailer took me to a solitary confinement cell, which was 2x1.20 metres wide and 3 metres high. It had a metal door, with a 15x15 cm. opening. Inside, there was a mattress on the floor. The cell had a malodorous smell and was dirty. I smelled cigarette smoke. There was no bathroom or toilet inside. There was a yellow light that was on all the time. I was held in the cell during the period of detention, which lasted for six days in a row… Three meals, breakfast, lunch and dinner, were provided to me. I considered them bad, insufficient, and unhealthy. At night, although there were blankets, I was so cold in the cell. These blankets also smelled awful and were unclean. My left leg hurt due to the extreme cold. Inside the cell, I suffered from respiratory distress. I asked an interrogator to relocate me to the rooms, but he refused and said there was not space there. During the period of my detention by the Preventive Security agency, I had no contact with my family, neither in person nor by telephone. No Palestinian lawyer visited me at the Preventive Security headquarters. I only had a COVID-19 test on Sunday, 20 December 2020; that is, five days after detention. I had the test at the Zawata COVID-19 testing centre, west of the city.[24]

Additionally, Palestinian security agencies attacked and/or banned nine peaceful assemblies in 2020. These were as follows:

- On 15 February 2020, multiple security agencies used force to disperse a peaceful assembly organised by the Hizb at-Tahrir (Liberation Party) in the city of Jenin. The assembly was held in protest against the Deal of the Century. Some parties claimed that the demonstration was dispersed because protestors insulted the PA and that a licence had not been issued to organise the peaceful assembly.

- On 15 March 2020, the Palestinian Police dispersed a peaceful assembly by force in the city of Rafah. The assembly was set to protest against using two of the city schools as quarantine centres in anticipation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Feeling apprehensive, the city residents protested against this measure. In response, the authorities dispersed the protest.

- On 8 July 2020, the General Investigations Department banned an information symposium by Fatah in the city of Gaza. The authorities claimed that the movement had not received a permit to hold the symposium, so it was banned. The event was scheduled to be organised indoors, rather than in a public place.

- On 24 July 2020, the Palestinian Police dispersed a gathering of worshippers in prayer in the town of Birqin, Jenin. The official authorities alleged that the gathering was dispersed because it violated COVID-19 preventive measures, which banned gatherings. However, the imam claimed he had obtained an authorisation from the Police to hold the prayers on condition of distancing.

- On 18 June 2002, the Palestinian Police dispersed a family protest in the Al-Bureij refugee camp. The Police attempted to execute a court decision to remove family encroachments on a street in the refugee camp. Family members protested in response.

- On 5 September 2020, Palestinian Police personnel assaulted a family gathering in Beit Hanoun allegedly because it violated movement restrictions in the context of combating the COVID-19 pandemic. As an ambulance was late to transport a patient in critical condition to hospital, the family in quarantine gathered at the patient’s house and took him in a private vehicle to hospital. As a result, Police personnel physically assaulted the family members.

- On 12 June 2020, the Preventive Security agency banned a funeral wake house of the Secretary General of the Islamic Jihad Movement, Ramadan Shallah, in the town of Tammun. A number of rights holders were detained.

- On 24 August 2020, in the context of tightening control on Fatah activities in the Gaza Strip, the Internal Security agency banned a peaceful event organised by Fatah in the city of Gaza, on the grounds that no permit had been obtained. The event involved a ceremonial signature of a memorandum of understanding between the Journalists and Lawyers branch offices of the Fatah movement.

- On 19 July 2020, security agencies banned a sit-in protest against corruption in the city of Ramallah. Many movements had called for the protest, but security agencies banned it by force and detained a number of participants and organisers.

A. A. recounts his experience when security agencies dispersed a peaceful assembly in Rafah:

At about 8:00 am on Sunday, 15 March 2020, two cars of the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MoH) arrived at the Marmarah and Ghassan Kanafani governmental schools of the Ministry of Education in the town of Al-Nasser, northeast of the Rafah city. Both schools were to be prepared as mandatory quarantine centres for persons returning via the Rafah border crossing. As they informed me, this was a preventive measure against COVID-19. Upon learning this, at about11:00 pm, hundreds of the town residents, including youth, men, women and children, gathered in front of the schools in protest against the MoH decision and measure. The schools were in close proximity to citizens’ homes. A number of protestors burned wheel tyres on the Salah ad-Din main road opposite the schools. They also displayed banners, expressing their rejection of the MoH decision and measure… At about 3:00 pm, a large Special Police force arrived on some 16 Police cars… The force was led by Major General Tawfiq Abu Na’im, Undersecretary of the Ministry of Interior in Gaza. As soon as they arrived, Major General Abu Na’im ordered me to keep women out of the place. Police personnel started to disperse protestors by force. They chased and beat protestors with batons and rifle butts. Civil Defence teams extinguished the fire and moved the tyres away by two loaders. Meanwhile, young men threw stones at the Police personnel. Intermittent protests continued for several hours. The Police continued to chase and physically assault protestors. In addition to arresting a number of protestors, Police personnel opened fire in the air. They also raided a number of homes, including my brother’s, and beat inhabitants with batons and rifle butts. They assaulted women and children. I heard them shouting obscenities at citizens. They also arrested a number of citizens from their homes. At about 11:00 pm, the Police managed to disperse protestors by force… Police attacks resulted in the injury of some 12 citizens, including a child, who sustained bone fractures and contusions all over their bodies. Most of these were members of my family. They also arrested 54 citizens, including 15 children. These continue to be detained.[25]

The majority of human rights violations perpetrated by Palestinian duty bearers were committed by the police in the West Bank (106) and in the Gaza Strip (155); Preventive Security forces (159); Internal Security forces (148); and the General Intelligence (66).

|

Perpetrator |

Number of violations |

|

West Bank-based Police |

106 |

|

Gaza-based Police |

155 |

|

Preventive Security |

159 |

|

Internal Security |

148 |

|

General Intelligence |

66 |

Internally, most notable was the Persons with Disability Movement. Beginning on 3 November 2020, persons with disabilities declared an open-ended strike inside the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) offices, demanding a comprehensive health insurance that would cover all their needs. The sit-in protest and events continued for more than two months. Finally, on 14 January 2021, the Palestinian government approved the Regulation on the Comprehensive Health Insurance for Persons with Disabilities, marking the end of the sit-in protest.

In his sworn statement on the movement to Al-Haq, A. A. reports:

On 3 November 2020, a group of four men and women with disabilities and I declared a sit-in protest inside the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) offices in the city of Ramallah. We demanded a comprehensive government health insurance for persons with disabilities. Currently, there is no health insurance for persons with disabilities and their needs. We had already carried out a number of peaceful demonstrations in this context. These ranged from protests at the PLC offices to attempts to reach the Palestinian Council of Ministers office, which was far from the PLC. We held a sit-in protest at a distance of some 400 metres from the Council of Ministers. On more than 10 occasions, we tried to reach the Council of Ministers. Each time, the police, including anti-riot police, personnel blocked our access. They placed iron barricades along the road leading to the Council of Ministers… On Monday, 21 December 2020, it was time for the Palestinian Council of Ministers to hold a session. We knew that the Council of Ministers convened every Monday for decision making. We, protestors inside the PLC, decided to head for the Council of Ministers in order to officially request that ministers approve the Draft Regulation on Health Insurance, which we had proposed. We had already submitted the draft regulation to the Council of Ministers almost a month earlier. We were surprised that the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MoH) introduced changes to the draft regulation, which we had prepared, rendering it meaningless. For example, we demanded that needed medicines be distributed to persons with disabilities by the MoH. However, in the amendments it made, the MoH said: “In case the medicine is not on the list of medicines approved by the Ministry, the General Secretariat of the Council of Ministers shall establish a committee to examine if such medicine can be distributed or not.” Also, we proposed that the persons with disabilities be referred to medical specialists, who would determine relevant treatment and needs. However, the MoH did not accept this request and kept the matter in the hands of the current committee. It should be noted we have many reservations on that committee. They do not apply clearly defined criteria to determine the degree of disability.[26]

[1] See “The Legal Monitor”, Palestinian Forum for Israeli Studies (MADAR), at: https://bit.ly/3acWH3P.

[2] According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), in 2020, GDP dropped by 12 percent because of the COVID-19 pandemic. In various sectors, most economic activities declined in varying proportions. Approximately 66,000 workers lost their jobs, bringing the unemployment rate up to 27.8 percent. See PCBS, Dr. Awad Demonstrates the Performance of the Palestinian Economy during 2020 & the Economic Forecasts for the Year 2021, available at:

[3] MADAR, A Draft Law preventing imprisonment of soldiers who killed Palestinians during military service, available at: https://bit.ly/3nU5VFQ (in Arabic) (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[4] JLAC, Joint submission to EMRIP and UN experts on the Israeli policy of withholding the mortal remains of indigenous Palestinians, available at:

https://www.jlac.ps/userfiles/200622%20-%20Joint%20submission%20on%20the%20Israeli%20policy%20of%20withholding%20the%20mortal%20remains%20of%20indigenous%20Palestinians_22%20June%202020_FINAL.pdf(accessed: 18 January 2021).

[5] MADAR, Ban on the release of the bodies of Palestinian fighters, available at: https://bit.ly/3bNOPXH (in Arabic) (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[6] Ultra Palestine, “The Israeli Cabinet ratifies the total prohibition on release of the bodies of martyrs”, available at: https://bit.ly/3qoumNc (in Arabic) (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[7] Al-Haq, Affidavit I130/2020.

[8] Peace Now, Construction, available at: https://peacenow.org.il/en/settlements-watch/settlements-data/construction (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[9] Arab 48, “2020: 43 martyrs and the occupying authorities demolish almost 1,000 structures and confiscate thousands of dunums”, available at: https://bit.ly/39KVUWi (in Arabic) (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[10] MADAR, Draft law requiring referendum on any government decision to hand over lands around any settlement in the West Bank to an “alien entity”, and Draft law on the confiscation of lands on which settlements are constructed, available at https://bit.ly/38POq5g (in Arabic) (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[11] Araby 21, “50,000 Arab homes are under the threat of demolition in the Palestinian territory occupied in 1948”, available at: https://bit.ly/2LXXWdy (in Arabic) (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[12] The Arab Centre for Alternative Planning, Suspension of “parts of” Amendment 116 to the Planning and Construction Law (Chemnitz Law) is a very important step in the right direction, but is not enough, available at: https://bit.ly/39L8YuQ (in Arabic) (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[13] In relation to homes, Al-Haq is informed by two primary criteria: (1) the owner, and (2) status of the home as to whether it is inhabited or not. Accordingly, if three uninhabited housing units belonging to the same owner are demolished, Al-Haq considers of all three units as one home, combining their surface areas as one home. For example, in Wadi al-Humos, the Israeli occupying authorities demolished more than 70 housing units, with multiple uninhabited units belonging to the same owners. Hence, the surface areas of these units were combined and entered as 14 homes only. Likewise, Bedouin homes usually include more than one residential tent. Al-Haq counts all tents, which serve as rooms or other facilities such as kitchens or toilets, of the same structure and household as one home. For instance, if a family live in four tents, including two as rooms, one used as kitchen and the other as a toilet, these are all counted as one home.

[14] MADAR, Draft law preventing unaffected persons from filing petitions to the High Court against official decisions, https://bit.ly/2LIBmp (in Arabic) (accessed: 18 January 2021).

[15] After they receive demolition notices from the Israeli occupying authorities, many Jerusalemites are forced to demolish their own structures and homes by themselves to avoid additional fees and fines if the demolition is executed by the Israeli occupying authorities.

[16] In many cases, a commercial premise belongs to the same owner, but consists of, e.g., more than one barracks. This is counted by Al-Haq as one commercial premise despite the fact that it comprises several barracks, tents, or structures unless the owner or type of commercial premise is different. For example, if an animal farm is made up of three barracks, but are all owned by the same owner, the surface area of this farm is combined and entered into the Al-Haq databank only once. This is also the case of storage facilities, which form an integral part of a home. These are counted as an inseparable part of the home.

[17] Areas within the Israeli municipal borders of Jerusalem refer to the territory forcibly and illegally annexed to the Israeli Jerusalem Municipality. These are not part of Area A, B, or C according to the Oslo designation. Since 1967, by a Knesset decision, the occupying Power has appropriated and imposed its sovereignty over this area. In 1980, unlawful annexation was endorsed by a basic law passed by the Knesset.

[18] Hagar Shezaf, “Israel Rejects Over 98 Percent of Palestinian Building Permit Requests in West Bank's Area C,” Haaretz, 21 January 2020.

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israel-rejects-98-of-palestinian-building-permit-requests- in-west-bank-s-area-c-1.8403807(accessed 18 January 2021)

[19] Al-Haq does not provide a full documentation of these violations. Hundreds of abuses are documented as a representative sample, giving an indicator of the nature of these abuses.

[20] Al-Haq, Affidavit, I52/2020.

[21] Al-Haq, Affidavit, I274/2020.

[22] Al-Haq, Affidavit, I58/2020.

[23] Al-Haq does not provide a full documentation of these violations. Hundreds of abuses are documented as a representative sample, giving an indicator of the nature of these abuses.

[24] Al-Haq, Affidavit, P185/2020.

[25] Al-Haq, Affidavit, P37/2020.

[26] Al-Haq, Affidavit, P178/2020.